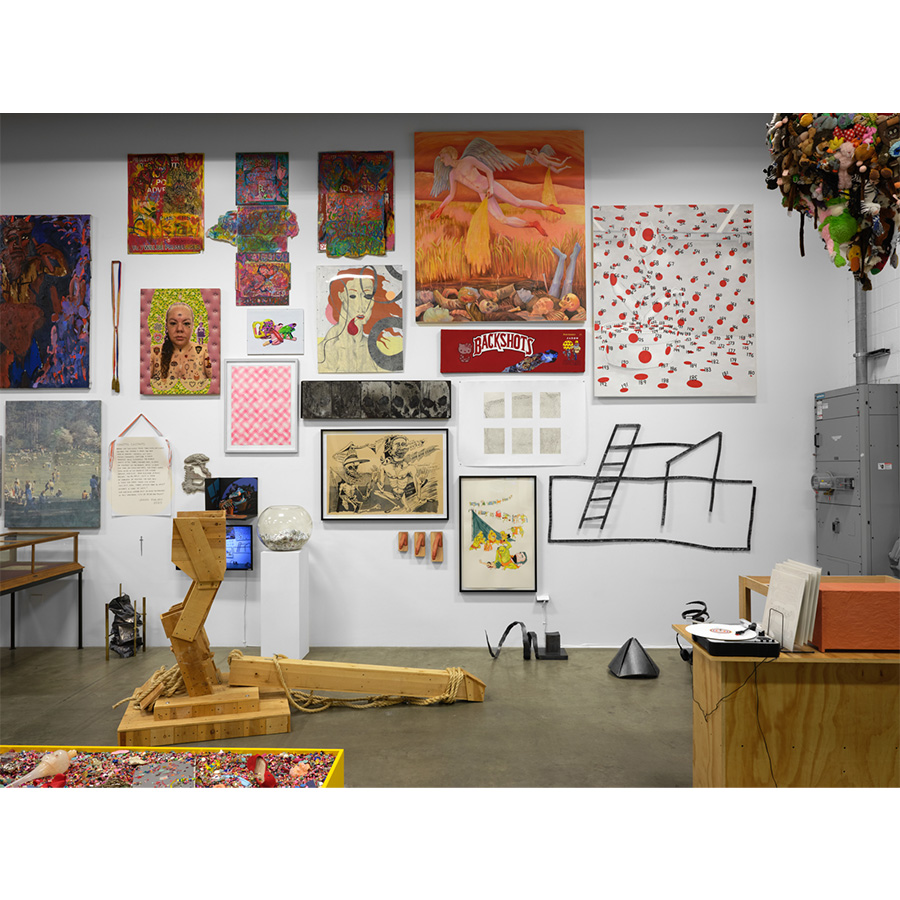

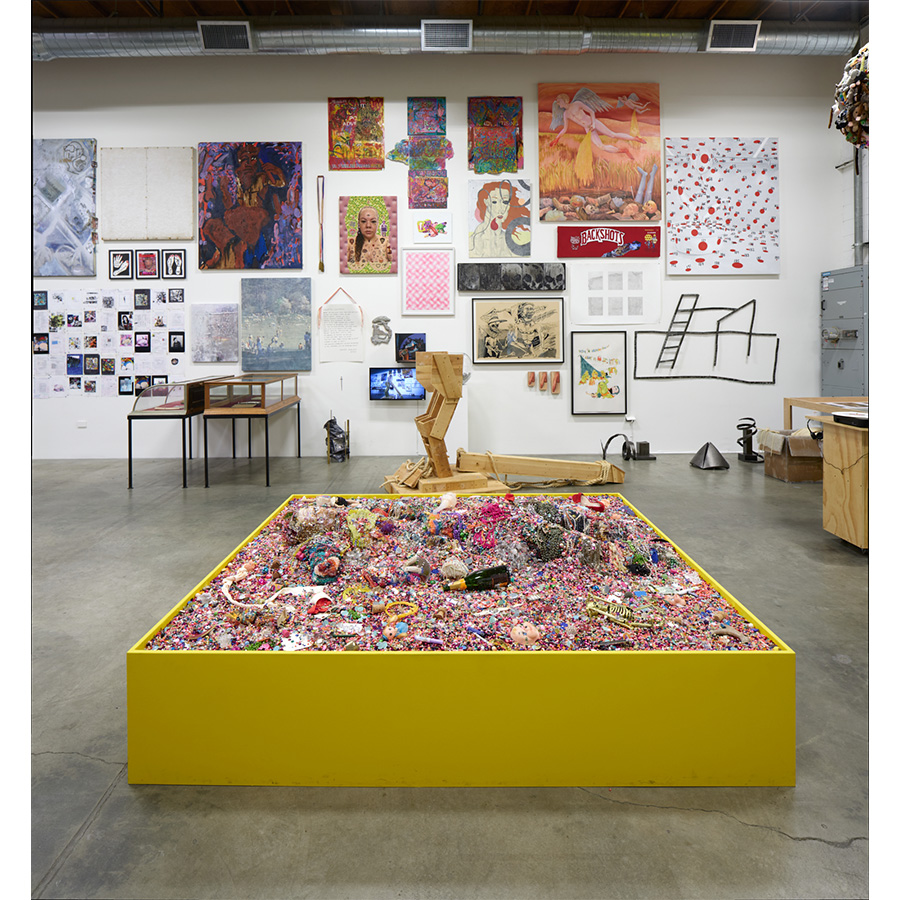

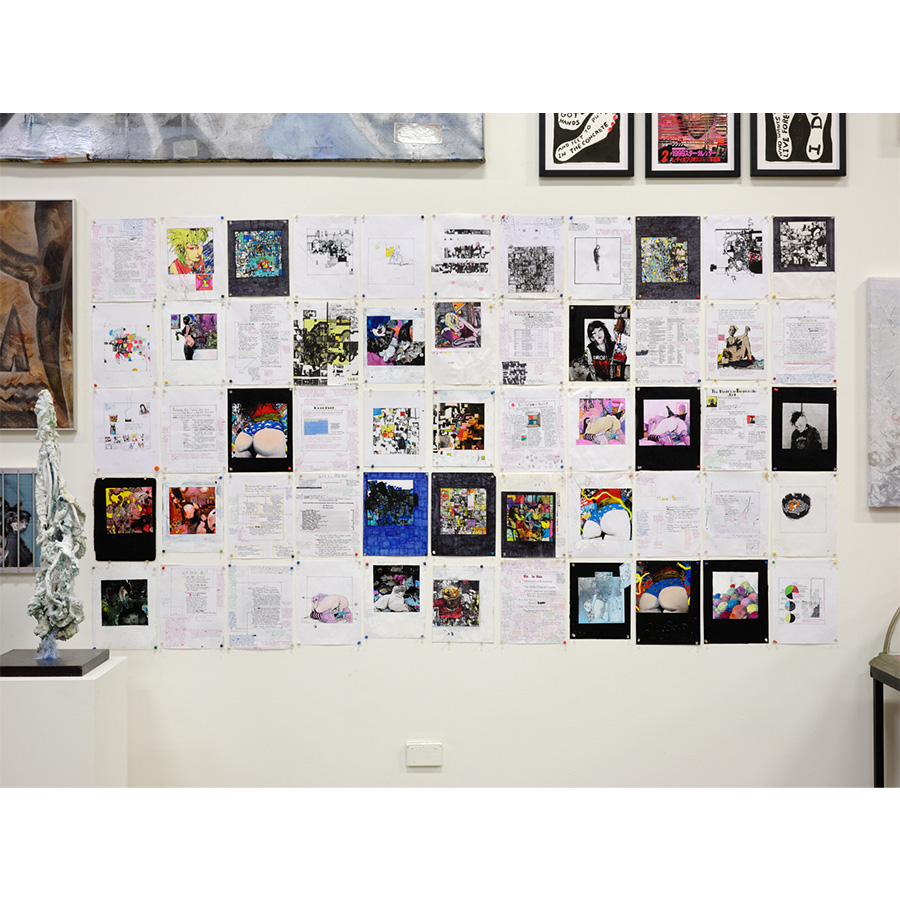

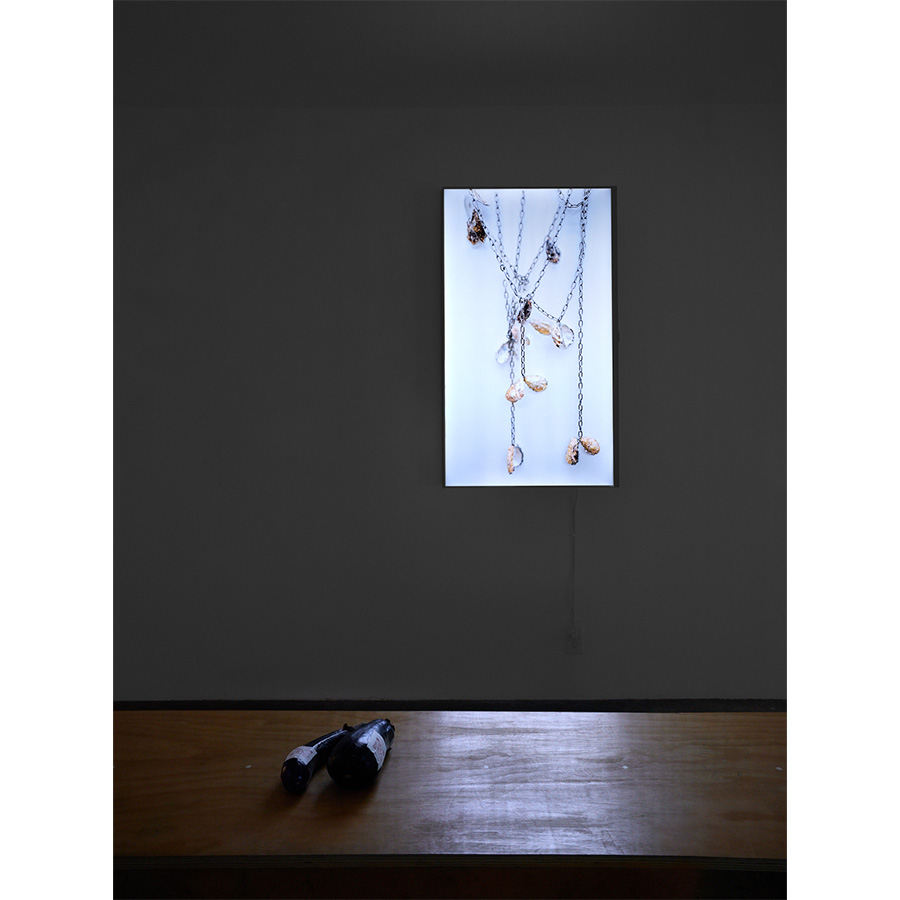

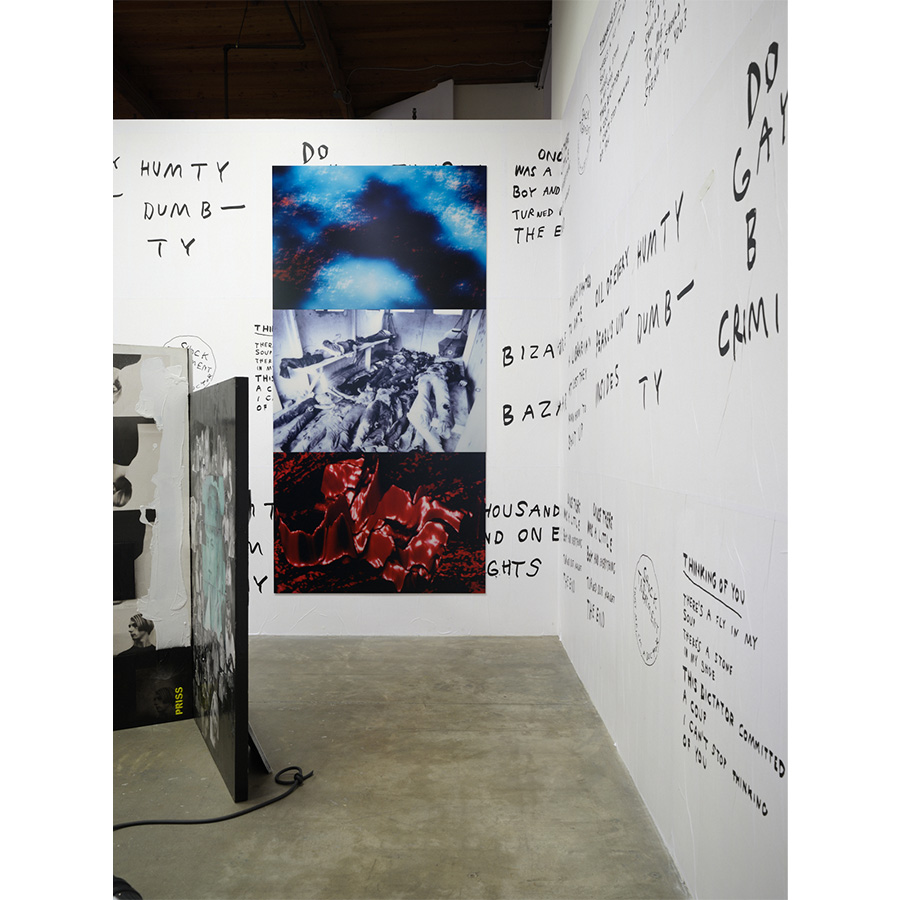

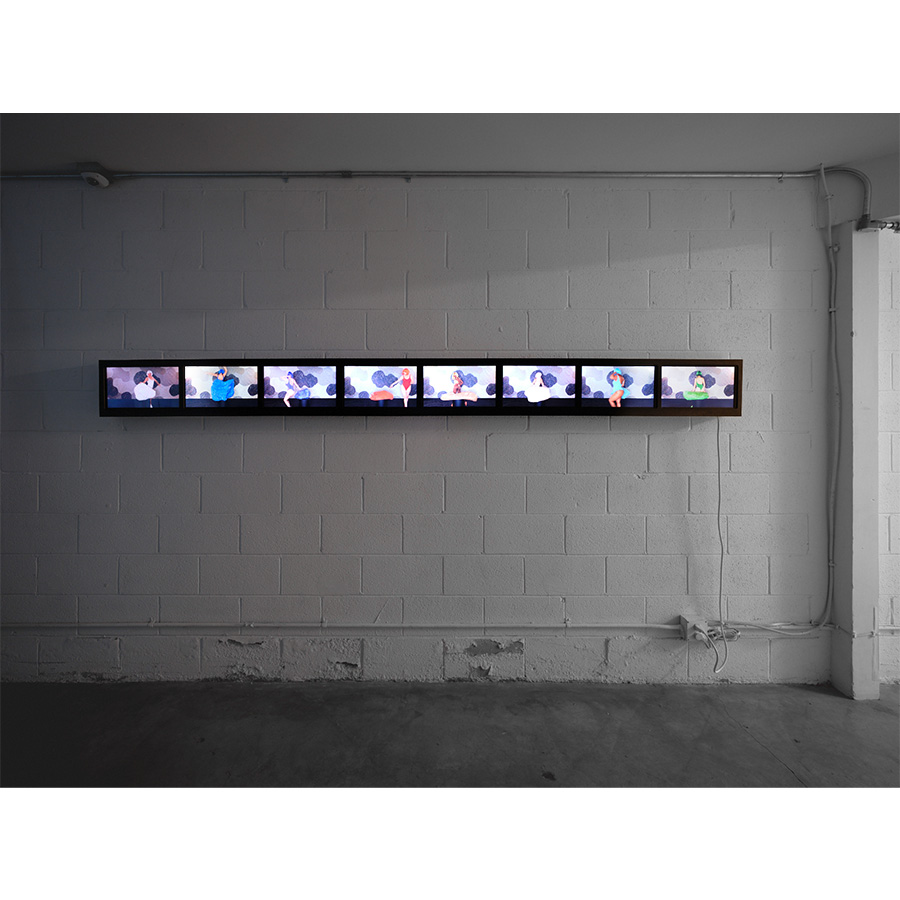

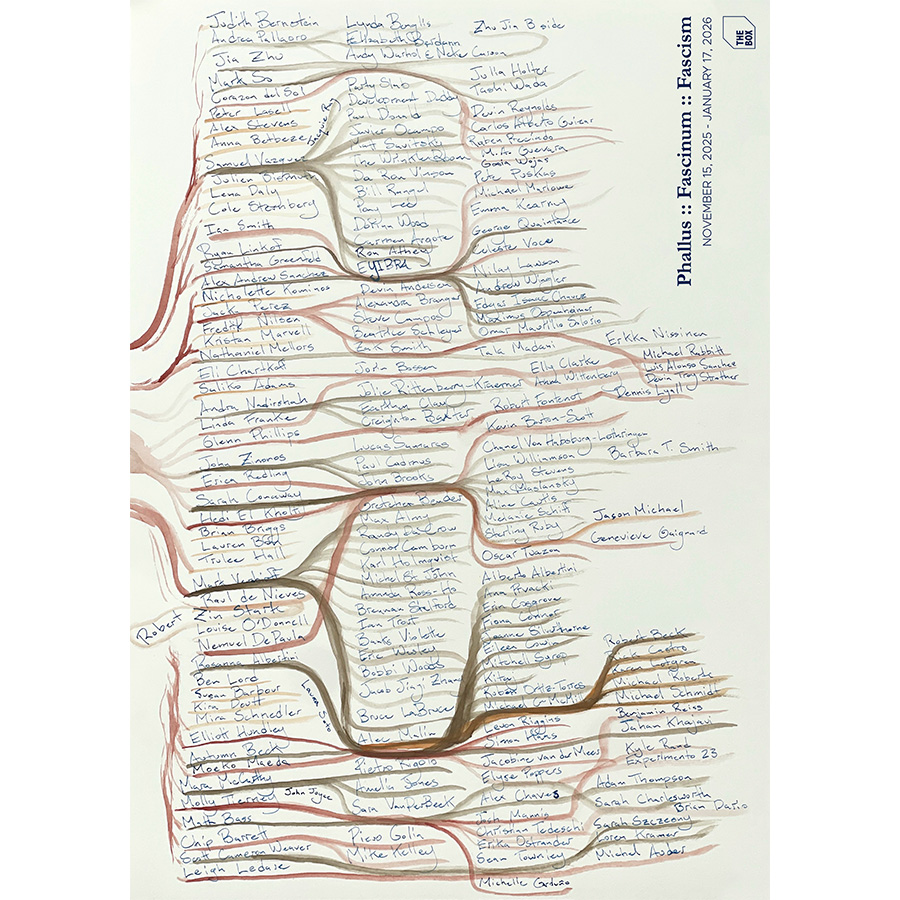

PHALLUS :: FASCINUM :: FASCISM

NOVEMBER 15, 2025 – JANUARY 17, 2026

OPENING RECEPTION

NOVEMBER 15, 5-8 PM

PERFORMANCE BY MARK SO WITH JULIA HOLTER AND TASHI WADA

5:30 PM

----

This is a show about inclusion as practice and process. Please invite whom you’d like.

To begin, please allow me some foreplay with wordplay;

The Greek root φαλλός (phallos) is likely related to the Proto-Indo-European root bhel-, meaning “to blow up” or “swell,” which connects it to concepts of inflation or enlargement. This same root appears in other words related to swelling or fullness, such as balloon, bellows, or belly.

A fascinum was an ancient Roman style of an amulet of a phallus, designed to draw away the evil eye from the user towards the amulet (because it was an object of desire). The English word "fascinate" ultimately derives from Latin fascinum and the related verb fascinare, "to use the power of the fascinus", that is, "to practice magic" and hence "to enchant, bewitch, or bind together”.

In ancient Rome, the fasces were a ceremonial symbol of authority carried before magistrates. They consisted of birch or elm rods bound together with a leather strap, often with an axe head protruding from the bundle. The fasces represented the magistrate’s power to punish (the rods for beating) and execute (the axe for beheading).

Benito Mussolini adopted this terminology when he founded the “Fasci di Combattimento” (Combat Squads) in 1919. The name deliberately evoked both the ancient Roman symbol of state power and the more recent tradition of Italian political organizing.

Now, I would like to draw your attention—at length—to the history of Ancient Roman militarism and fucking, or the suppression of non-procreative sex, if you please:

The endless demands of Roman militarism created an inexorable pressure for population growth that fundamentally transformed sexual culture and law. What began as pragmatic concerns about maintaining adequate military recruitment gradually evolved into a comprehensive system of legal and social controls that systematically suppressed non-procreative sexual behaviors. This transformation reached its culmination not with the end of paganism, but with Christianity’s adoption and intensification of these existing regulatory frameworks.

Before the ancient Romans, with the ancient Greeks and Egyptians, sexuality was notably pragmatic. In ancient Egypt homosexual relationships appeared in art and literature without moral condemnation, marriage was often informal, divorce was relatively easy for both sexes, and celibacy held no particular virtue—even priests typically married and had families. Greek attitudes toward homosexuality are well documented, celibacy and contemplative life often being elevated, with contraception and abortion discussed openly by medical writers. Homosexual relations between soldiers were even understood as beneficial to the intensity of their fighting.

The earliest manifestations of state intervention in sexual behavior emerged from Rome’s military expansion across

Italy. The Twelve Tables, codified around 450 BCE, established the legal framework of paternal authority (patria potestas) that gave fathers absolute control over their wife’s reproductive choices, their children’s marriages and even their reproductive choices. This wasn’t merely about family structure—it was about ensuring that each household contributed adequately to Rome’s military needs through the production of future soldiers.

As Rome’s territorial ambitions expanded, so did the censorial powers that monitored citizen behavior. The censors, initially concerned with property assessments for military service, gradually extended their oversight to include sexual conduct that might affect population growth. Social pressure against permanent bachelorhood among the patrician class intensified precisely during periods of military expansion, when the state most desperately needed the sons of prominent families to serve as officers and provide military leadership. Rome was mobilizing a staggering 10-15% of its entire adult male citizen population simultaneously (with 30-40% of the entire population being slaves, that were also recycled into their military).

The Punic Wars and subsequent Mediterranean conquests created unprecedented demands for manpower, coinciding with the first systematic legal attacks on non-procreative sexuality. The Lex Scantinia, likely enacted during this period of military crisis, criminalized certain homosexual acts, particularly those involving freeborn Roman men as passive partners. The law’s timing was no coincidence—Rome was simultaneously fighting Hannibal and expanding eastward, requiring every citizen male to fulfill his reproductive and military obligations. Growing taboos against practices like fellatio and cunnilingus were similarly justified as “foreign” and unmanly behaviors that weakened Roman military character.

The crisis of the late Republic, marked by civil wars and recruitment difficulties, intensified state intervention in sexual behavior. The Lex Iulia de Adulteriis Coercendis, building on earlier precedents and finalized under Augustus in 18 BCE, criminalized adultery not primarily for moral reasons, but to ensure legitimate heirs who could provide military service. The law’s provisions carefully protected the patrilineal transmission of military obligations from father to son.

Increased prosecution of sexual behavior deemed to undermine traditional family structures accompanied Rome’s desperate attempts to maintain military recruitment. Social campaigns against Greek sexual practices, particularly symposium culture and pederasty, were explicitly connected to Roman military superiority over their allegedly effeminate Greek subjects. The message was clear: sexual discipline was military discipline, and military discipline was the foundation of Roman power.

Augustus’s reign marked the systematic codification of militaristic sexual regulation. The Lex Iulia de Maritandis Ordinibus of 18 BCE mandated marriage for men aged 25-60 and women aged 20-50, with explicit exemptions only for those serving the state in ways that precluded family life. The Lex Papia Poppaea of 9 CE penalized celibacy and childlessness through inheritance restrictions, creating economic incentives for reproduction that directly served military recruitment needs.

The legal privileges granted to parents (ius trium liberorum) provided those with three or more children with significant legal advantages, including exemptions from certain civic duties and enhanced inheritance rights. These privileges were explicitly calculated to encourage the production of future soldiers. Restrictions on marriage between social classes served to maintain distinct citizen bloodlines suitable for military service, while increased regulation of prostitution channeled sexual activity toward procreative marriage rather than sterile commercial encounters.

The early Imperial period saw the expansion of stuprum laws targeting non-marital sex among citizens, creating comprehensive legal frameworks that made non-procreative sexual activity increasingly criminal. The senatus consultum against castration under Domitian around 83 CE explicitly protected male reproductive capacity, recognizing that voluntary sterility represented a direct threat to military recruitment. Legal restrictions on divorce were made more stringent under various emperors, ensuring that marriages, once contracted, would continue to produce children for military service.

The military crises of the third century intensified sexual regulation as the empire struggled to maintain adequate forces against barbarian invasions and internal rebellions. The Lex Cornelia de Sicariis was expanded to include severe penalties for castration, treating voluntary sterilization as a form of treason against the state’s military needs. Legal campaigns against mystery religions that practiced celibacy reflected imperial recognition that religious enthusiasm could undermine demographic objectives.

The cultural apparatus supporting these legal frameworks became equally comprehensive. Literary campaigns by authors like Juvenal and Martial satirized sterile relationships and non-procreative sexuality, while philosophical schools promoted marriage and childbearing as fundamental civic duties. Mystery religions emphasizing fertility, such as those devoted to Cybele and Mithras, gained state support precisely because they reinforced demographic objectives. Public festivals celebrating fertility and procreation, architectural programs emphasizing family and childbearing, and educational reforms emphasizing masculine virtue tied to reproductive success all served to normalize and institutionalize the connection between sexual behavior and military obligation.

The legalization of Christianity under Constantine in 313 CE and its subsequent establishment as the state religion represented not a break from these regulatory traditions, but their crystallization and intensification under new ideological justifications. Early Christian leaders, far from rejecting the Roman system of sexual regulation, embraced and expanded it while providing new theological rationales for existing practices.

The Christian synthesis represented the ultimate triumph of Roman demographic anxieties over sexual freedom. By transforming military necessity into divine commandment, Christian sexual ethics preserved and expanded the regulatory apparatus that Roman militarism had created, ensuring its survival well beyond the collapse of Roman military power itself. The theological justification of procreative obligation proved more durable than the military justification from which it had originally emerged, creating patterns of sexual regulation that would define Western civilization for more than a millennium.

Finally, to be enjoyed with your bedside smoke (and a faggot meant a bundle of sticks or tobacco leaves, to be burnt)—the word proletariate came from the ancient Roman census, which categorized the class of people that had no other assets but the ability to procreate.

R.Z.S.

FULL PARTICIPANT LIST:

Saliko Adams

Rosanna Albertini

Alberto Albertini

Max Almy

Devin Andersen

Carmen Argote

Ron Athey

Michel Auder

Jose Barajas

Susan Barbour

Chip Barrett

Math Bass

Creighton Baxter

Robert Beck

Autumn Beck

Gretchen Bender

Lynda Benglis

Elizabeth Berdann

Natalie Bergman

Judith Bernstein

Anna Betbeze

Julien Bismuth

Lauren Bon

Jorin Bossen

Kevin Bouton-Scott

Alexandra Branger

B. A. Briggs

John Brooks

Michael C~ McMillen

Paul Cadmus

Connor Camburn

Steve Campos

Rick Castro

Aline Cautis

Simion Cernica

Sarah Charlesworth

Eli Chartkoff

Alex Chaves

Edgar Isaac Chavez

Elly Clarke

Earthen Clay

Sarah Conaway

Fiona Connor

Diva Corp

Erin Cosgrove

Eileen Cowin

Randy Du Crow

Development Daddy

Lena Daly

Brian Dario

Nemuel DePaula

Paul Donald

Kira Doutt

Hedi El Kholti

Experimento 23

EYIBRA

Tatiana Echeverri Fernandez

Robert Fontenot

Linda Franke

Genevieve Gaignard

Michelle Garduño

Piero Golia

Samantha Greenfeld

M. A. Guevara

Carlos Alberto Guizar

Simon Haas

Chanel Von Habsburg-Lothringen

Trulee Hall

Derrick Harlan

Karl Holmqvist

Julia Holter

Elliott Hundley

Zhu Jia B side

Amelia Jones

John Joyce

Emma Kearney

Mike Kelley

Jahan Khajavi

R.B. Kitaj

Nicholette Kominos

Loren Kramer

Marcus Kuiland-Nazario

Bruce LaBruce

Drake LaBry

Suzanne Lacy

Peter Lasell

Nilay Lawson

Leigh Ledare

Pony Lee

Ryan Linkof

Karen Lofgren

Ben Lord

Dennis Lyall

Tala Madani

Moeko Maeda

Alec Malin

Josh Mannis

Michael Marlowe

Kristan Marvell

Max Maslansky

Emily Mast

Mara McCarthy

Jacobine van der Meer

Nathaniel Mellors

Jason Michael

Vijar Mohinda

Andra Nadirshah

Raul de Nieves

Fredrik Nilsen

Erkka Nissinen

Louise O’Donnell

Javier Ocampo

Maximus Oppenheimer

Rubén Ortiz-Torres

Erika Ostrander

Andrea Pallaoro

Jacky Perez

Pau S. Pescador

Glenn Phillips

Elyse Poppers

Ruben Preciado

Ana Prvacki

Pete Puskas

George Quaintance

Michael Rabbitt

Kyle Rand

Bill Rangel

Jacquie Ray

Erica Redling

Benjamin Reiss

Devin Reynolds

Levon Riggins

Pietro Rigolo

Jolie Rittenberry-Kraemer

Michael Roberts

Amanda Ross-Ho

Sterling Ruby

Lucas Samaras

Luis Alonso Sanchez

Alex Andrew Sanchez

Matt Savitsky

Melanie Schiff

Beatrice Schleyer

Michael Schmidt

Mira Schnedler

Jeanne Silverthorne

Party Slab

Zak Smith

Ian Smith

Barbara T. Smith

Mark So

Corazon del Sol

Omar Maurilio Solorio

Laura Soto

Michael St John

Brennan Stalford

Cole Sternberg

Alex Stevens

LeRoy Stevens

Devin Troy Strother

Mitchell Syrop

Sarah Szczesny

Christian Tedeschi

Adam Thompson

Molly Tierney

Sean Townley

Ian Trout

Oscar Tuazon

Elizabeth Valdez

Sara VanDerBeek

Johannes VanDerBeek

Samuel Vazquez

Mark Verabioff

Da Ron Vinson

Banks Violette

Celeste Voce

Tashi Wada

Scott Cameron Weaver

Eric Wesley

Lisa Williamson

Andrew Wingler

Anna Wittenberg

Gosia Wojas

Dorian Wood

Bobbi Woods

THE WRINKLE ROOM

Jacob Jiayi Zhang

Jia Zhu

John Zinonos

Robert Zin Stark